Afraid of losing their grip on power, some leaders—including President Trump—are doing whatever they can to keep people from casting their ballots.

At 1,777 square miles, Harris County, Texas, is larger than the entire state of Rhode Island. With 4.7 million residents, it’s the third-most populous county in the United States. Traffic in and around its county seat of Houston is notoriously terrible; during rush hour, driving from one end of the city to the other can easily take two to three hours. So in the midst of an election coinciding with a deadly pandemic, county officials decided to provide several drop-off locations where voters could submit their ballots. They settled on a dozen sites, thoughtfully distributed throughout the vast county.

Then, on October 1, Texas Governor Greg Abbott announced that all but one of those sites must shut down. Through an executive order, the governor is now allotting a single drop-off location for every one of Texas’s 254 counties—regardless of its population or size. Unless lawsuits can stop Abbott’s executive order in the courts, it will force tens of millions of Texans to travel extraordinarily long distances in order to drop off their ballots early. (How big are some Texas counties, you ask? One west Texas county, Brewster, stretches across nearly 6,200 square miles, an area larger than Connecticut.) In a statement, Abbott has claimed that the meager number of drop-off sites “will help stop attempts at illegal voting.”

In fact, what the Texas governor did last week was an act of “brazen voter suppression,” says David Daley. A senior fellow at FairVote, a nonpartisan organization that champions voting reform, and the author of Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy, Daley sees Texas’s shuttering of hundreds of ballot drop-off locations as only the latest surprise in a year marked by “voter suppression whack-a-mole.” To stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic, voters enthusiastically embraced voting by mail. “Then you saw an assault on the post office” by a postmaster general with suspiciously close ties to the national Republican Party, Daley says. Voters then enthusiastically embraced the idea of drop boxes. “And suddenly, there were lawsuits and efforts to limit those,” he says. “Every solution that has been presented to solve the problem of how to make it easy and safe to vote during a pandemic has been challenged by Republicans—who have wanted at every step of the way to make it more difficult and more dangerous.”

In a year where experts are predicting record-breaking voter turnout, Trump and many of his supporters know that they’ll lose in a fair fight—which is why it’s so important for voters to know their rights and to make sure that any suppressive tactics fail. Already, residents of Harris County are proving themselves to be an unflappable bunch: On Tuesday, the first day of early voting, they had cast more than 128,000 votes by the time the polls closed at 6 p.m., shattering the county’s early-voting “opening day” record of 68,000. But the heavy turnout there comes in spite of the governor’s efforts—not because of them. Many of those votes, in fact, were cast safely via drive-through voting, something Texas Republicans had been trying to stop before a judge deemed their case “frivolous.”

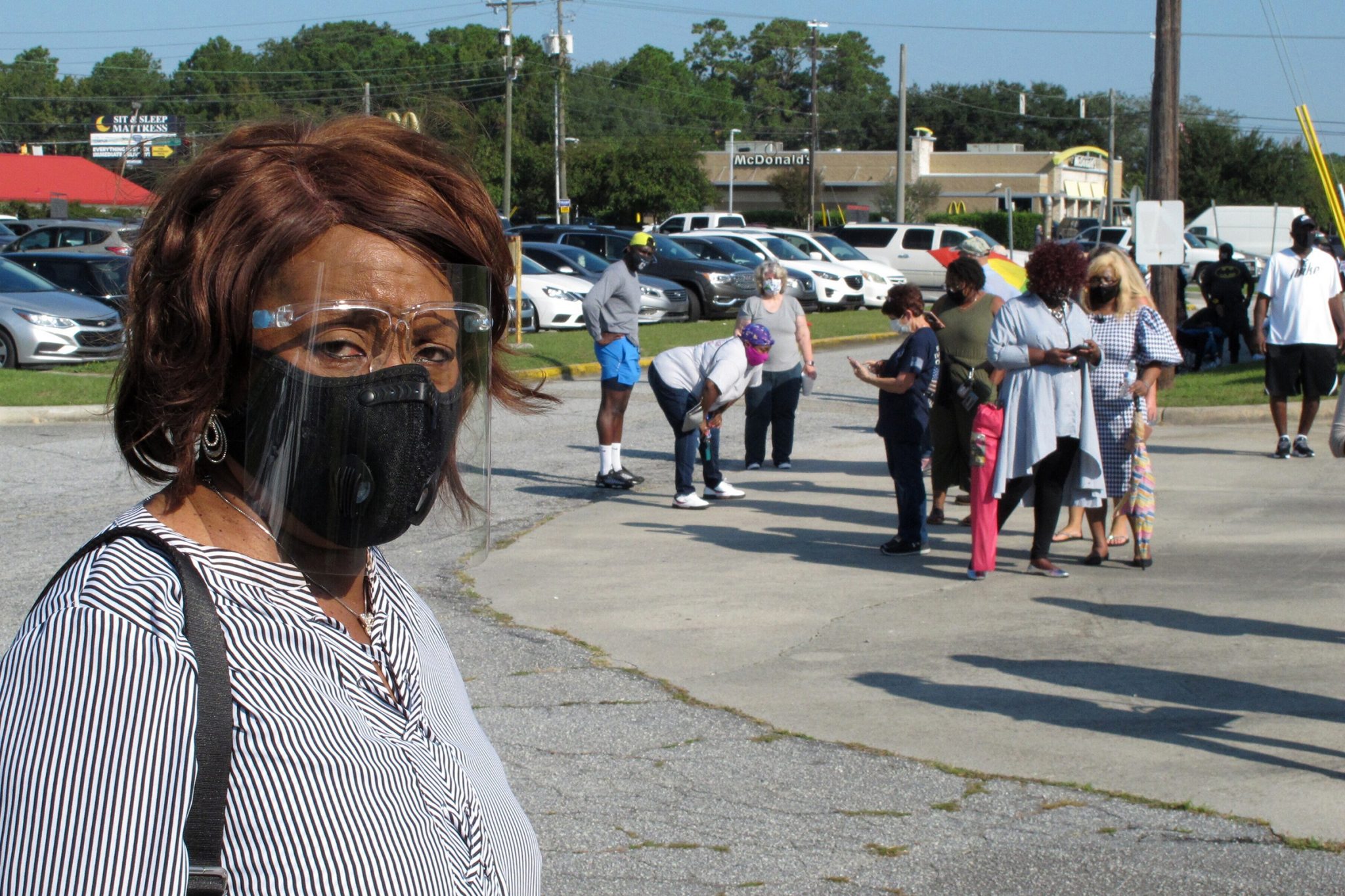

Voter suppression in America is as old as American democracy and has taken many forms: among them, poll taxes meant to discourage the poor, “literacy tests” carefully designed to make the test taker fail, orchestrated disinformation campaigns, and egregious identification requirements targeting Latino and Black voters. In this election, voter suppression has evolved to take the form of abruptly shutting down drop-off locations, spreading baseless rumors about voter fraud, requiring former felons to pay fees before casting their vote, and even encouraging voter intimidation at the polls. Disturbingly, President Trump himself is deploying some of these tactics. Among a torrent of tweets Trump sent out last week was one calling for volunteers “to be a Trump Election Poll Watcher” and linking out to the bellicosely named “Army For Trump” website. Along with Trump urging his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully” at the first presidential debate, the tweet has caused many to worry that the president is essentially inviting mayhem.

“It’s deplorable,” says Myrna Pérez, director of the Voting Rights and Elections Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. She sees the president’s goal as twofold: to rally his supporters, obviously, but also “to scare and deter voters.” Historically, such tactics have been used to keep people of color away from the polls.

According to Pérez, state and county officials whose aim is to disenfranchise voters of color (who, by and large, lean Democratic) don’t have to cook up grandiose plans to achieve their goals. They just have to make it harder and slower to vote, knowing that voters of color are more likely to have responsibilities at work or at home that prevent them from spending hours in line. “Voter suppression is going to hit marginalized communities the hardest,” Pérez says, “because—by definition—those are the communities that have the fewest margins to be able to absorb any kind of abuse.” These same disenfranchising officials, she adds, “know that if they put barriers or burdens in front of everybody in a precinct or a county, there are going to be some communities that have a harder time overcoming them.”

That’s why early and mail-in voting are so crucial to helping people avoid such hurdles and making sure that their voices get heard. Studies have shown that long wait times for voters are indeed a deterrent: In 2012, they may have led to between 500,000 and 700,000 people dropping out of line before voting. And the longest wait times tend to be in communities of color. One study revealed that as the percentage of voters of color in a precinct increased, so too did the average wait time—and dramatically so. In precincts that were 90 percent white, the average wait time in 2018 was five minutes. In precincts that were 90 percent voters of color, it shot up to 32 minutes, more than a sixfold increase.

And voting suppressors are using this knowledge to their advantage. Freelance “poll watchers” don’t have to physically or verbally threaten voters in order to wreak havoc, says Daley. The well-documented shortage of poll workers nationwide, combined with the unprecedented logistical challenges to in-person voting posed by the pandemic, already means that lines on Election Day are likely to be long. “If you have a dramatically enhanced Republican operation to question voter registrations, you could slow down lines and the basic administration of the polls.”

Since 2013—the year that the U.S. Supreme Court decided, in Shelby County v. Holder, to ease federal restrictions on states seeking to purge voter rolls, close polling places, enact stringent voter ID laws, and limit early voting—more than 1,700 precincts have closed in more than a dozen states, with a disproportionate number of these closures occurring in predominantly Black counties. Fewer voting places lead to longer lines at those that remain.

But along with this strong voter engagement and determination, there are plenty of reasons to be hopeful. Daley notes that were Democrats to take control of the Senate in the upcoming election, the Senate would likely vote on the For the People Act, which would expand voter rights and which the U.S. House of Representatives has already passed. He’s also hopeful that we might someday soon see the right to vote enshrined in the U.S. Constitution—something many Americans already assume to be the case but actually isn’t. And Daley is optimistic that a new president, working with a Democrat-led Senate, would act quickly to reauthorize and modernize the original Voting Rights Act, legislation that the House has already passed and renamed the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act in honor of the late congressman and civil rights leader.

Pérez is optimistic too—based on what she’s seeing right now, all across America. Early-voter turnout is already breaking records, and analysts are predicting historic levels of participation. Despite some people’s best efforts, “voters are refusing to be intimidated,” she says. “They’re making it very clear that they care about their fundamental right to vote, and they’re not going to allow some self-appointed policers of the polls get in the way of their casting a ballot that will count.”